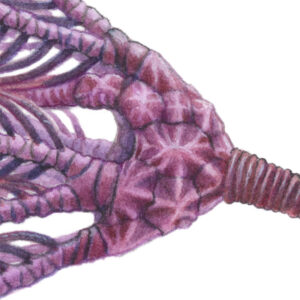

I recently completed this watercolour and gouache painting of the Ordovician crinoid Konieckicrinus josephi:

Illustration of crinoid fossil Konieckicrinus josephi © Emily S. Damstra

The painting shows the crinoid (sea lily) reconstructed, with its arms splayed and stem curved as if feeding in a current. Its stalk is attached to a bit of hardground on the sea floor, among some marine detritus including the remains of two different species of brachiopods and one edrioasteroid. The hardground is depicted as fossilized rather than reconstructed. In between the reconstructed crown of Konieckicrinus josephi and the hardground below is a painting of an unreconstructed fossil crown of the same crinoid species.

Crinoids are relatives of starfish and sea urchins, and they still exist today. Known as feather stars, a stemless variety of crinoids can be found among coral reefs; see illustration here. The stalked sea lilies are found in the deep sea; see illustration here. Paleozoic crinoids, however, were far more diverse and abundant than crinoids are today.

The Challenges

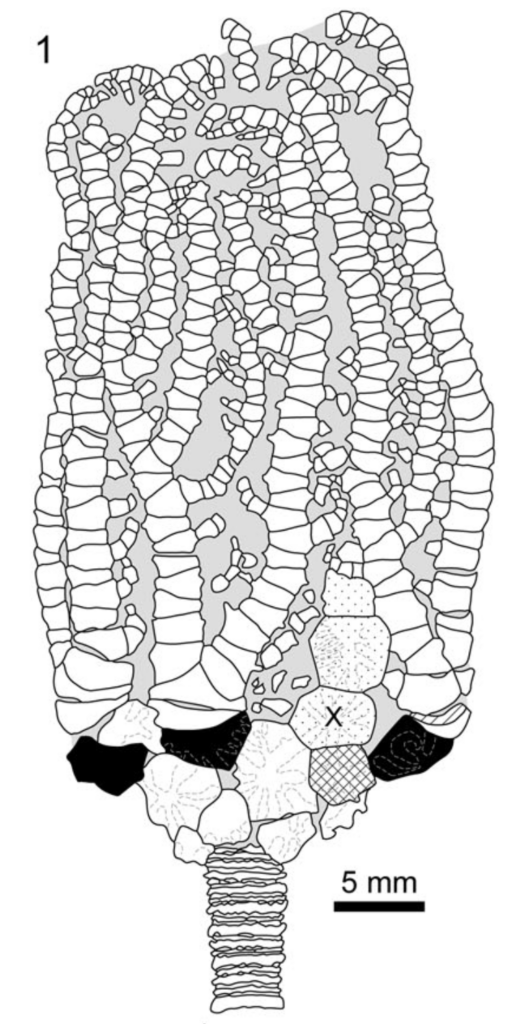

Reconstructing fossil invertebrates is one of my favorite types of illustration projects. It’s especially rewarding to see an animal “come to life” that’s never previously been imagined as a living animal. Konieckicrinus was one of those. Prior to my rendering, the only existing drawing was a black and white scientific diagram of a closely-related species, which depicts a fossil specimen rather than a reconstructed animal, and it only shows the crown and a small portion of the stem:

A diagram of the Ordovician crinoid Konieckicrinus brechinensis from Wright et al. 2019; Biodiversity, systematics, and new taxa of cladid crinoids from the Ordovician Brechin Lagerstätte

Aside from that diagram and the scientific description, I had access to some fossil specimens as well as some photographs of fossil specimens. Here’s one of the photos:

Photo of Ordovician crinoid fossil Konieckicrinus josephi © Joseph Koniecki

Reconstructing this crinoid species was daunting, and involved learning a whole new glossary of anatomical terms in order to interpret its scientific description and be able to discuss the species with a scientist. Some of this terminology is esoteric enough that it’s not available online (that I could find), so I had to consult the extensive and detailed 1978 publication “Skeletal Morphology of Fossil Crinoids” by Georges Ubaghs in the Treatise of Invertebrate Palaeontology. Fortunately, I live near a university that has a copy of that volume.

Once I had a basic understanding of the anatomy, it was still a challenge to put together the pieces. Each calyx plate bears ornamentation and has an irregular shape and specific placement. The arms branch a certain way, the numerous arm segments each (with a few exceptions of course) bear a pinnule, and even some of the pinnules branch. The pinnules are actually segmented too, but the small size of my illustration meant I could only suggest this segmentation. I felt relieved when the sketch finally came together!

I was grateful to have the generous assistance of palaeontologist Dr. Selina Cole, who gave me guidance about the curve of the stem, the stem columnal pattern, the accuracy of the calyx plates and arm segments, and more. She was one of the authors of the paper that originally described Konieckicrinus josephi, along with other Ordovician crinoids.

Close-up of the reconstructed calyx of Konieckicrinus josephi

The story of the Ordovician crinoid fossil

It was fossil collector and fossil art enthusiast Joe Koniecki who commissioned this painting. He has spent a great deal of time collecting fossils from the Brechin quarries in Ontario, Canada (see his book Pictorial Guide to the Fossils of Brechin, Ontario Area). Of the well over a thousand crinoid specimens he’s found, only about 20 or so were the crinoid that paleontologists Lena Cole, Davey Wright, and William Ausich later described and named Konieckicrinus josephi. “You can just imagine the excitement in the field,” said Joe, reflecting on his realization that he had found an unknown species. Having a genus and species named after him is “the highest honor an amateur could receive” according to Joe, who finds it rewarding that his passion for invertebrate fossils can contribute to science. He explains: “The professional community has a negative perception of collectors. I am glad to be one of many collectors that have made significant contributions towards paleontology and alleviate some of the negative perception.”

In the Brechin quarries, collecting superb fossil specimens is rarely as easy as picking them off the ground. It involves carting in a rock saw and cutting the fossils out of larger rocks, which might be resting at odd angles on huge piles. It takes experience to recognize what might be a worthwhile specimen, and to decide where and how to cut the rock. And then the specimens need to be hauled out of the quarry, carried into Joe’s basement, and cleaned. Joe explains: “Cleaning the fossils from Brechin involves using scribes and an air abrasive machine with a microscope.” It’s time-consuming. Some before and after photos, along with the equipment used, can be seen at Joe’s website here. All that is to say: There is a very significant investment of time and money into the whole process. That kind of dedication makes collectors like Joe a valuable resource to paleontologists who recognize the potential for collaboration.

Having donated some of the K. josephi specimens to a museum for posterity, Joe felt that a painting of the species named after him would be a fitting memento. Joe isn’t the first to have commissioned artwork for such a situation; see this ammonoid, this polychaete, and this birdstone. I love being a small part of these stories.

4 Comments

Comments are closed.

Fabulous — as always, Emily!! You have done Joe proud.

I appreciate your feedback, Dave!

Emily,

Your skill as an artist of invertebrate paleontology reminds me of the art contributed to medicine by Frank Netter (Medicine’s Michelangelo). Both of you treasures in your fields of interest!!

John

John, I’m honored by such a comparison! Thank you.