There’s no doubt that Alexander Graham Bell’s invention and then commercialization of the telephone in the late 19th century had—and continues to have—a major impact on peoples’ lives. His experiments took place in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, so it’s fitting that the Massachusetts dollar in the United States Mint’s American Innovation $1 Coin series highlights the invention of the telephone.

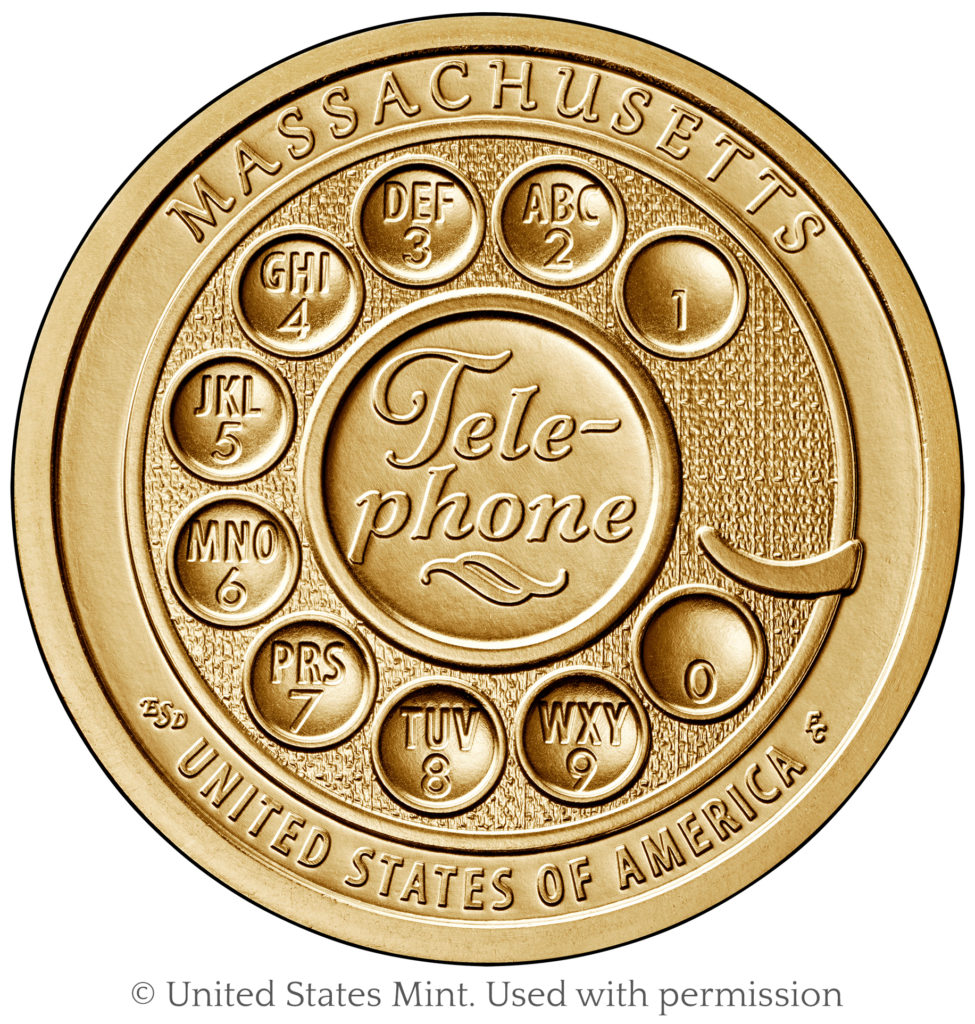

The Statue of Liberty graces the obverse side of all coins in this series, and the reverse side commemorates innovations. I designed the reverse side of the Massachusetts coin, and Eric David Custer at the United States Mint engraved it.

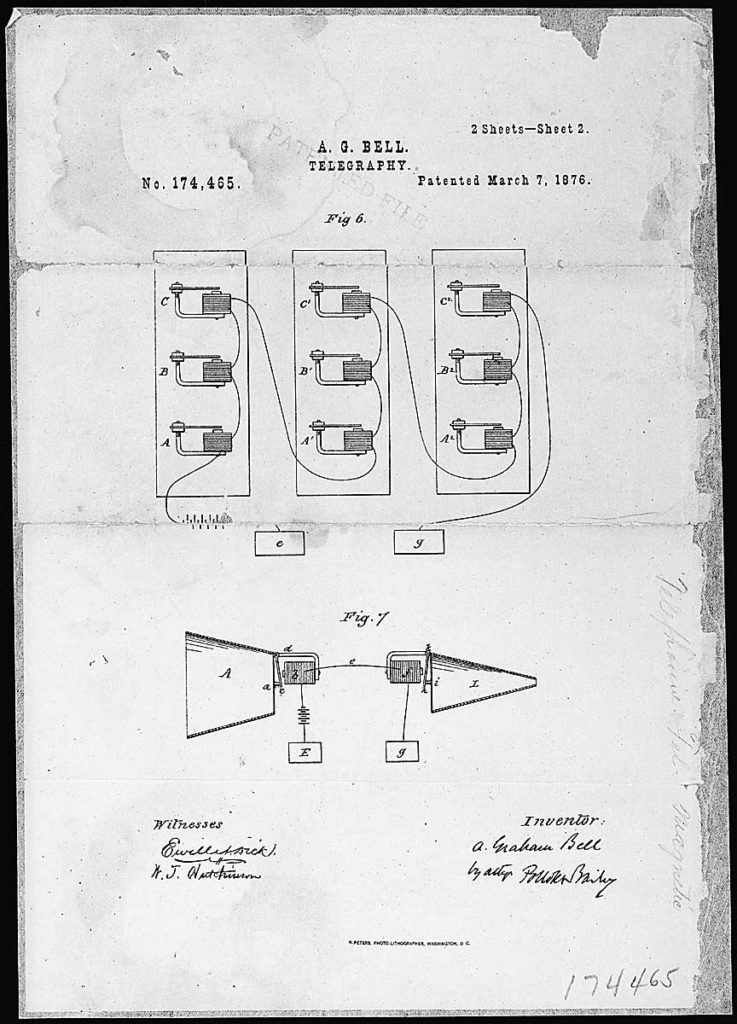

It’s a straightforward design showing the dial of an early rotary telephone. I ultimately landed on this design idea after sifting through many images of early telephones, including the diagram in Bell’s original 1876 telephone patent:

Initially, I despaired that the very earliest telephones, like the one in the patent, are unrecognizable as telephones by most people today and therefore not very useful as symbols. Then, while browsing images of some early 20th century rotary telephones, it occurred to me that the dials didn’t change much throughout the many decades when rotary phones rang in households and offices everywhere. The earliest phone I can recall from my childhood home had a rotary dial, and it was around long enough into the 1980s that I remember using it. I felt that the dial would be immediately recognizable as part of a telephone by most people alive today,* either by direct experience or through photos, And, because it hearkened back to fairly early in the history of the phone, I thought it was a good icon to symbolize this innovation. As a bonus it is the perfect shape for a coin. 🙂

I love it when I come across surprising bits of trivia during my research for any illustration project. While reading about the invention of the telephone, I learned that the development of area codes in the mid 20th century is linked to the phone hardware of the time—a rotary dial. The Bell engineers who devised the area codes aimed for maximum efficiency, so they assigned area codes with the most easily dialed numbers to the largest metropolitan areas. New York City was 212, Chicago was 312, Los Angeles was 213, etc. Thus, the most frequently dialed area codes took the least amount of time to dial on a rotary phone, due to the arrangement of numbers counter-clockwise around the dial.

This excellent article in The Atlantic discusses the history of phone numbers and area codes in detail, and it’s a story surprisingly rife with emotion.

Apparently one can still buy a functioning rotary phone (see here), though it does require a landline.

*Although younger generations who haven’t used a rotary phone will likely recognize it as a phone, that doesn’t mean they know how to use it. There are some entertaining YouTube videos showing teenagers trying to dial a number on a rotary phone, such as this one. I don’t blame those teens for not being able to figure it out immediately; I’m not sure it’s an intuitive procedure.