We all have pet peeves, even though there’s a lot going on in the world that makes them pretty insignificant. While acknowledging that there are many more important things in life, I write this post about my own personal illustration pet peeve in the hopes that maybe, just maybe, it’ll make a little teeny difference. Here goes:

I love butterflies. They’re one of my favorite subjects to illustrate and one of my favorite sights in nature. To me, they’re a symbol of hope, an embodiment of beauty, and a sign of what’s right in the world. I think that’s why it bothers me when depictions of butterflies often fail to do them justice, whether they are in a work of art, a website, a product, an animation, or in print.

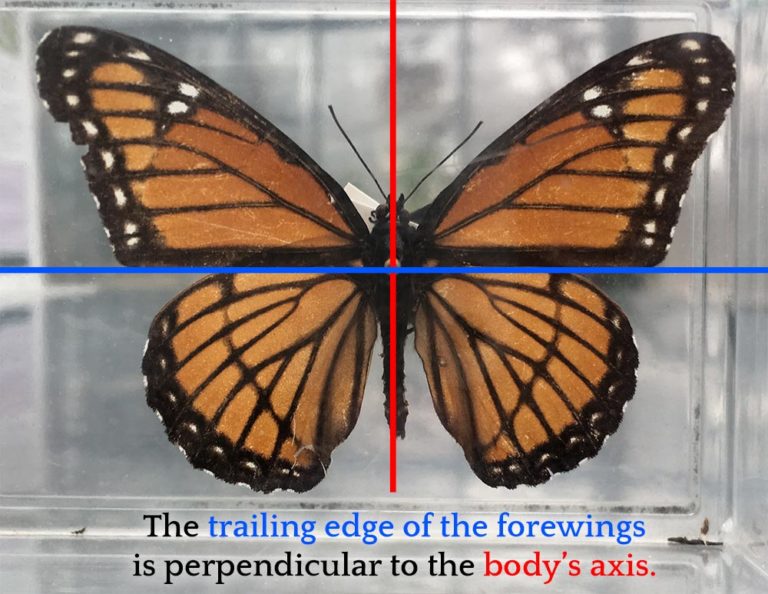

My explanation needs to begin with a description of a dead butterfly. When a butterfly is placed in an insect collection, the person who prepares it positions its wings according to a convention that facilitates identification. In the photo of a dead, pinned butterfly below, note that the trailing edge of the forewings (blue line) is perpendicular to the body’s axis (red line). When the insect has just been killed, it remains flexible for awhile, allowing the collector time to insert a pin and manipulate its wings into this position, where they are held in place until they become dry and stiff. This is an unnatural position for the wings; it’s a pose that may be possible for the insect to assume in life, but not a position that most species typically assume.

Photo of pinned Viceroy © Emily S. Damstra

In field guides and other butterfly reference materials, one frequently sees images of such pinned butterflies because, I presume, it is easy to photograph a dead butterfly. Also, numerous photos of dead butterflies against the same background is aesthetically consistent, and the pinned position allows the viewer to see as much of the hind wings as possible, aiding identification. It is a useful convention and it makes sense in field guides.

By contrast, butterflies that are alive and going about their business of flying and nectaring do not typically hold their forewings too far forward of their head. In life, the way a butterfly holds its wings is variable, but it is uncommon for most species that I’ve encountered to hold their forewings in the manner of pinned specimen. Here are some photographs I’ve taken over the years that demonstrate this:

Viceroy, alive! © Emily S. Damstra

butterfly photos © Emily S. Damstra

As you can see, in most cases, it is the leading edge of the forewings that is nearly perpendicular to the body. One will notice quite a bit of variability in wing positions in living butterflies, but it’s atypical for the trailing edge of the forewings to be perpendicular to the body. This is true not only of butterflies that are perched, but also of butterflies aloft. As an example, view this photo of monarchs in flight. There are exceptions, of course. It seems that some of the smaller butterflies may exhibit wing positions fairly close to that of a dead, pinned specimen:

Pearl crescent photo © Emily S. Damstra

Eastern Tailed blue © D. Gordon E. Robertson CC BY-SA 3.0

I suspect that the field guide photos of dead, pinned butterflies are the ultimate (though unwitting) source of my pet peeve: The pervasive phenomenon of butterflies in popular culture being shown as dead, with the trailing edge of their forewings perpendicular to their body. Here are some examples:

You can see at this link that the practice of illustrating dead butterflies goes back a long way, in a painting by a 19th century artist.

A particularly ironic example is this movie poster for a documentary about the flight of monarchs. Some of the flying monarch illustrations are accurate, but the largest and many of the others are clearly dead, even though they’re depicted as if in flight.

Stock photography sites include misleading photos of dead butterflies purporting to be in flight. Here’s one. Here’s another. It’s understandable that customers would accept the description as accurate, even though it isn’t.

This website shows numerous butterfly tattoos. Only a few look alive, despite the tattoo artists’ clever technique of inking cast shadows to give the impression that the butterflies are actually perched on the skin. Had the recipients of dead butterfly tattoos known the difference between a living and a dead butterfly, I have to believe they would have more carefully considered their options. I think a depiction of a living butterfly is the most effective way to convey its positive symbolism.

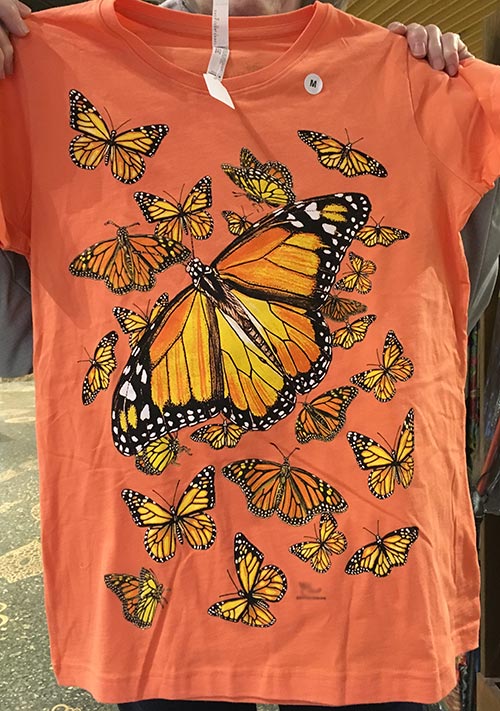

Dead butterflies are frequently spotted in gift shops. You can rest your head against them, adorn your ears with them, hang them on your wall, enoy them while you sip a beverage, wrap your gifts with them, or wear them:

Dead butterfly on a pillow

Dead butterfly earrings

Dead butterfly wall hanging

Dead butterfly thermos and bottle

Dead butterfly ribbon

Dead butterflies on a t-shirt. At least the largest one and some of the others look alive…

I have blurred a couple company names in the photos above because I’m not trying to shame anyone. Most people have seen and are influenced by thousands (millions?) of depictions of unintentionally dead butterflies and have never considered the difference between a living and a dead butterfly. That’s why I decided to write this post.

I’m not innocent of committing my own pet peeve. In 2001, I illustrated the endangered Karner Blue butterfly using pinned specimens as a reference:

Karner blue butterfly illustration © Emily S. Damstra

Had I realized then what I know now, I would have changed the wing and leg positions to be more lifelike. It would have made for a better representation, even though I was not attempting to show the insects in flight or perched on a flower. Nowadays, if you ask me to illustrate a butterfly, I will position its wings as if it is alive:

Monarch butterfly illustration © Emily S. Damstra

Red admiral illustration © Emily S. Damstra

I realize there are some instances where it isn’t clear that the artist/designer intended to show a living butterfly, and where it may be perfectly acceptable to represent a dead butterfly. Nonetheless, there’s no good reason to depict a dead butterfly in the vast majority of situations. It doesn’t take much effort to be accurate about wing position. My hope is that the multitudes of butterfly images in our culture will gradually shift toward alive, which is how I prefer to think of them, and how I think these beautiful insects should be seen.

If you hadn’t previously noted the difference between a living and a dead butterfly, I’m afraid you will now begin to see dead butterflies EVERYWHERE, as I do.

28 Comments

Comments are closed.

Thanks so much for this enlightening post. It has changed the way I view images of butterflies.

Don’t professionals pin a bit to the side, instead of the vertical middle?

Dante, I believe that is true when pinning several other groups of insects, but not Lepidoptera. However, I’m not an authority on that, so don’t quote me!

[…] Read Full Story […]

Maybe it helps to think of illustrated butterflies as a kind of iconography? If you work with little kids (especially girls) one of the first things they learn to draw is “a butterfly” (meaning, a dead butterfly). It will not have anything like natural coloring, and might have big friendly eyes, but will definitely have two curling antennae and spread, uplifted wings. It’s a heraldic image, like a lion rampant. Lions don’t look like that, but the symbol says what it needs to. Just a thought.

I appreciate your comment, Sharon. In my view, the reason kids would draw a butterfly in the pinned position is solely because it is (unfortunately, I argue), ubiquitous in popular culture. I have no problem with stylization, but one can represent a butterfly in a stylized way with the wings in life position just as easily as with the wings in pinned position. I think a heraldic lion, while perhaps not true to life, is still regal and an appropriate symbol. By contrast, I think a butterflies in life position make for more meaningful iconography than ones in pinned position.

You photographs of “lifelike” butterflies (wings back) show the bufferflies perched. Is it possible however that, during flight, the wings do actually flap to a more forwards position? I’ve tried to check a few slo-mo videos, it does seem to depend on the species a little but while hovering and descending, butterflies’ wings do seem to come forwards more than when they are perched at rest (the wings tend to trail the head when taking off and climbing).

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Nick. Please see my reply to Arthur’s comment on this post.

Interesting article, but is this issue a pet peeve? I fear it is a bug a boo.

I feel totally ruined because soon after reading this I saw a post on FB with a picture of a beautiful dead butterfly held in someone’s fingers, with the caption:

“The butterfly is a living symbol of Christ. It begins it’s life among us, then “dies” and is wrapped in a cocoon until it is raised, glorified! The butterfly is also a beautiful reminder of those who are no longer with us, but with god.”

I mean, a lovely sentiment of course, totally ruined (or made totally hilarious) by my new awareness of dead butterflies.

Indeed!

It looks like you want to make a point that dead butterflies always have their wings stretched like that. I’m pretty sure some of those other butterflies in the pics were also dead, just had their wings at a more natural position.

Thanks, foo. Perhaps I should have better emphasized the point that the dead butterfly position I’m referring to is the conventional one used for insect collections. Of course, when butterflies die naturally and there is no one to collect them, their wings do not end up like those in my photo of the pinned Viceroy. Aside from that photo, all of actual butterflies in my photos were alive.

I got a good chuckle and an education out of this. I kept seeing it on hackernews and finally clicked on it. Glad I did, and despite the title, not what I expected. I used to photograph butterflies at every opportunity and I never noticed the wing positions.

Thanks. I noticed that there is quite a variety of comments on the subject at Hacker News. https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=14460013

Of course you’re correct that the rigid spread posture is not “lifelike.” And you are correct that it goes back to the early 19th Century. It was adopted as the standard mounting posture for museum specimens for the specific reason that it maximizes the exposed wing surface, giving visual access to all or nearly all elements of the pattern. Since the point of field guides is to facilitate visual identification, it’s not surprising that many older ones use the museum-spread posture in their illustrations. However, the trend is strongly away from that. Digital photography has made it much easier to photograph live butterflies in the wild, and most field guides in print today use either photographs or art drawn from photographs of live butterflies. My own “Field Guide to Butterflies of the San Francisco Bay and Sacramento Valley Regions” (UC press, 2007) has magnificent paintings (by Tim Manolis) of everything in lifelike poses (except a handful of skippers that are exceedingly difficult to sight-ID). By the way, the biggest Monarch in the movie poster is not in a dead pose. It’s actually in mid-wingbeat.

Before digital photography there was quite a bit of fakery of butterfly pictures, even in respectable magazines. It was usually very easy to spot the fakes. Not only were the wings in unlifelike positions, but the compound eyes had turned brown or black (they would usually be greenish or bluish in many species in life)–and sometimes one could see the hole in mid-thorax where the pin had been artfully removed!

Did you know Vladimir Nabokov was both a sophisticated Lepidopterist and a skilled artist? He drew them in flight or in museum spread depending on the use/purpose of the drawing. An antiquarian bookseller once showed me one of VN’s novels in which he had drawn a butterfly on the flyleaf. He asked me if I could identify the butterfly. I told him it was an anatomically-correct swallowtail, but one that God had not gotten around to creating yet.

Thank you for sharing your comments and experiences, Arthur. I haven’t had the privilege of seeing your book, but it pleases me to know that you worked with an artist and that his paintings show the butterflies in life positions. I too have noticed that more recent field guides show butterflies in life positions, and I’m very happy about that. I did know that Nabokov was a Lepidopterist, but I wasn’t aware that he was also an artist. How interesting!

I respectfully disagree the movie poster’s largest monarch is in mid wing-beat. As others have pointed out in the comments (Nick and Rick), at least some butterflies do actually move their forewings significantly forward of their head while in flight. See the link Rick posted, with his excellent in-flight photo at the bottom of that page, and see also this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odvYot6Rldw

At 9 seconds in, the maximum extent of the insect’s downstroke, one can see that the forewings are quite a bit forward of the head. However, in Rick’s photo as well as in the video, we are seeing the insect from the side. Seen from the top, the wings would look quite different from that of a pinned specimen and from the movie poster example due to their downward-pointing angle. (Also, the large butterfly in movie poster has a very narrow abdomen, an additional clue that the reference used for it was likely a dried specimen).

While I agree with the overall sentiment of the article, I feel I should point out what I feel is an error in fact. Nick and Arthur have already mentioned that a butterfly’s wings will move forward in flight. I normally photograph butterflies at rest, but I have photographed a few in flight, and the wings can be in all sorts of positions, including the “wing forward” position the author decries. I dug up one such photo, and placed it on one of my web pages for anyone who is interested in viewing it. Scroll down on this page:

http://www.ontariobutterflies.ca/families/pieridae/large-marble

Thanks for your comments and link to photos, Rick. I recognized your name as the author of the Pocket Guide to Butterflies of Southern & Eastern Ontario; kudos to you for that resource, as well as for creating your excellent Ontario Butterflies website.

I stand by my assertion that the pinned position “is an unnatural position for the wings.” For an explanation, please see the reply I just made to Arthur’s comment.

Very enlightening! Thank you! I also enjoyed reading the commenters’ various positions on butterflies’ wings in flight.

Very interesting article. We need to see nature as it really is. Next you can write an article about how lemmings don’t really commit mass suicide. What would ever possess the Walt Disney company to even come up with that idea in the first place?

Good question!

I agree that the abdomen in the movie poster is ridiculously narrow. The wing position could be “frozen’ in flight and is not intrinsically false. By the way–Rick may be interested to know that the Large Marble has gone regionally extinct in my part of California, where it was formerly common to abundant. We do not know the cause. The timing coincides with the widespread use of neonicotinoid insecticides–in fact, as we have published, a general regional butterfly decline coincides with that–but correlation does not prove causation. The Large Marble had been a great success story in adapting to the Anthropocene, breeding on the superabundant naturalized wild mustards after its native valley-grassland host, California Mustard (Guillenia lasiophylla) became very rare. So its loss is especially striking.

[…] Please, enough with the dead butterflies! (hn) […]

I noticed this on a bag I have. I used to volunteer at a butterfly exhibit and know one of the butterflies well and the drawing has it spread too far, exposing a hindwing edge that is in a different color. You would never see it in real life.

I totally understand you this is your pet peeve, and the dead butterflies perching in tattoos do look a bit off.

I don’t really share your distaste for dead butterflies in art however. I work in a museum and have spent hundreds of hours pinning moths and butterflies. Entomological collections held in museums have their own kind of beauty in my eyes. I love classifying and collecting and when I take photographs of my collections, perfectly preserved, symmetrical specimens are particularly appealing.

The idea that dead butterflies do not equal art doesn’t sit right with me, because art is subjective and the meaning you assign to living vs dead butterflies is personal.

For field guides, I agree that it can be more useful to have pictures of butterflies in their natural poses. This butterfly book: https://www.allenandunwin.com/browse/books/general-books/natural-history/The-Butterflies-of-Australia-Albert-Orr-and-Roger-Kitching-9781741751086 is great for that. The artist Albert Orr painted the entire life cycles of each of the butterflies of Australia, all in their natural conditions, which is really useful for identification.

ps. your art is really beautiful 🙂

Thanks for taking the time to write, Louise. I appreciate everyone’s perspective on this. You’re right that art is subjective, and as I said in my post, there are times when it is appropriate to depict a butterfly in the dead, pinned position. I agree with you that butterflies in that pose can indeed be beautiful, since I tend to think that all butterflies are inherently beautiful. The point I was trying to make is that so many of the images we see of butterflies are of dead butterflies, and I don’t believe that the people creating those images realize that they’re depicting dead butterflies. In many instances, it is obvious that the artist/illustrator/sculptor/etc. was attempting to depict a butterfly in a lifelike way – such as perched on a flower or flying – but didn’t understand that the ubiquitous spread-winged pose is actually that of a dead, pinned butterfly. I think if more people understand the difference between how a live butterfly holds its wings compared to how a collector positions them, we’ll see more lifelike depictions of butterflies.

Thanks for the link to the Butterflies of Australia book; it’s good to hear that it includes of images of butterflies in natural poses.

Emily,

Your mom suggested the blog to me and I found your thoughts and responding comments interesting. Art Shapiro stated comments I might have made well. He is one my favorite scientist in the world and unfortunately I rarely see or visit with him.